Point of interest (9) Plaça de l’Àngel.

But let’s go back a further four centuries prior to this, when this square was the southern gate of the entrance wall to the city. This wall was built over the Romans’ wall. Recently, when undergoing works to improve the traffic conditions on this avenue, the remains of Roman citizens were found; at that time they would have been buried outside the walls.

The avenue that we have before us is Via Laietana, in memory of the Iberian tribes living in this area before the Romans. In the 8th century, this door witnessed fights and heroic acts. Let the watchman tell us some of these stories.

Legend of the Reconquest of Barcelona.

In the 8th century, the Moors came to Catalonia and became lords of the Barcelona plain and part of the nearby regions, but the city had not yet been conquered. The attack of the Saracens was expected at any moment.

The knights who had gathered in the city, with the count, thought it was opportune to stay outside the walls to see if they could beat the Moors and thus avoid an attack on the city. Gathering as many men-at-arms as possible, they left for the castle of Guanta, near Caldes de Montbui, a village several miles to the north, where the Catalan forces planned to get organised and meet with the knights who were fleeing from the Moors, and they awaited them in open terrain.

The count had a Moorish father and daughter in his palace as servants, they signalled their comrades outside the city walls with lanterns, so when the Catalan forces came out, the Moors had already been warned, and they were waiting for the knights on the Matabous plain, located not far from Barcelona. A hard battle ensued, in which many Catalans perished and few survivors remained. The count managed to escape and run towards Guanta, where he met the other knights. The Moors chased them. If the count entered the castle of Guanta, the castle would fall too and the count would be taken prisoner. To escape danger, he hid in a cave near the fortress, still known today as the count’s cave, but he was discovered. In accordance with war etiquette, the Moors cut off his head. In Barcelona, the rest of the nobility awaited the result of the battle, since they depended on it. The news did not take long to reach them.

The triumphant Moors reached the gates of the city, and with a crossbow, according to one version, or an arrow, according to others, they launched the count’s head from outside the walls into the city. It was thrown near where we are now, Carrer Bassea. It is believed that this name, which has no meaning in today’s language, comes from crossbow, in memory of the instrument used by the Moors to launch the head of Count of Borrell II.

At that time the count’s palace was located near the walls and the head landed on one of the palace terraces, precisely at the feet of the Countess of Borrell, who was waiting for news of her husband.

Another tradition tells quite a different story. The Arabs had invaded our land with savage fury, the city of Barcelona had been totally devastated and reduced to ruins, all the noble knights and men-at-arms had to flee, together with their Count of Borrell.

In the city of Manresa a number of knights and nobles met and decided there to start another battle against the Moors. They asked the Pope to help them with more Christian knights and promised at the same time to grant honours and lands to all who put their weapons at the orders of the Count of Borrell’s decimated forces.

The help received was very little, to be able to stand up to the tall, strong Moors. As the knights prepared to start battle a tall and well-built young man appeared, wearing white clothes and a large red cross on his chest and another similar one on his shield, and armed with a well-sharpened spear.

The battle began. The young man was riding a white horse. The unknown knight launched himself like fire between the lines of the Moors, dealing blows of the sword left and right, causing dozens of Moors to fall, scattered and mortally wounded. The unknown knight fought furiously and did such damage to the Muslims that they soon withdrew and made it easy and possible for the Christians to once again enter the city of Barcelona, which they had lost a few days before. All the strong fighters were impressed by the bravery of the unknown knight, and among them, they wondered who he could be, since nobody knew him or where he had come from.

The Christian forces came in triumphantly through the coastal gate in the city wall, located near Plaça de l’Ángel, led by the unknown knight, who despite all the blood from the combat still wore his white clothes and red cross, and bore a shining shield.

When the knight reached the middle of Plaça Sant Jaume, at that time small and narrow, his horse of fire became flesh and bone. The knight held his spear towards the sky, made the sign of the cross three times and disappeared.

All the knights who fought with him believed that it was Sant Jordi (Saint George), who had wanted to defend and save Catalonia from the Muslims. All the knights adopted him as their patron saint and his cross became part of the coat of arms of Barcelona as well as many other cities and towns.

Before starting wars, knights entrusted themselves to Sant Jordi and always obtained great protection, especially if they were fighting non-believers. His intervention is attributed to many battles, and to cliffs and banks, where the footprints of his fire horse’s horseshoe are shown as a sign of his passing and a memory of his miraculous intervention made of weapons. Our warriors fight to the cry of Jordi to receive the saint’s protection. In some cases, the knight who invoked him turned his horse into fire like the saint’s and broke through the lines of the enemy, causing terrible destruction, as if it were himself.

The walls protected the city, but the sea was always an open door to other civilizations, the Phoenicians, the Greeks and the Romans. The entrance door of the wall in the Middle Ages led to the Ribera neighbourhood, so called because it is on the shore of the Mediterranean Sea; it was the door to the sea, to fishermen, to other towns. Here we see the angel pointing her finger at the canon who had wanted to keep a relic of Eulalia, the patron saint of Barcelona. In the distance and in front of the port, we see the jewel of Santa Maria del Mar.

Category: Barcelona walking Tags:

Contact and Booking

Mobile: +34649970408 pere.sauret10@gmail.com

Experiences

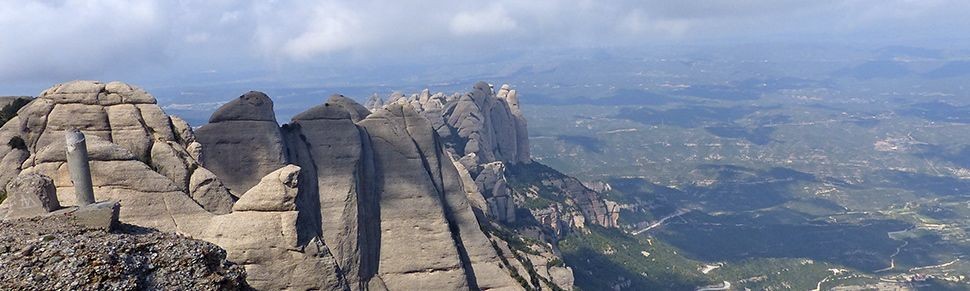

Hiking Walking Rock-climbing

Donate

Copyright © 2025 · All Rights Reserved · BarcelonaWalking Barcelona Hiking Barcelona Montserrat Costa Brava Pyrenees

Adventure Theme by Organic Themes · WordPress Hosting · RSS Feed · Log in

BarcelonaWalking Barcelona Hiking Barcelona Montserrat Costa Brava Pyrenees

BarcelonaWalking Barcelona Hiking Barcelona Montserrat Costa Brava Pyrenees